This is a theorem that has always fascinated me. Usually tucked away into an obscure part of a math textbook that we just flip over, it took me a while to realize the sheer brilliance and beauty of this piece of math. Wouldn’t it amaze you to know how our brains have inherently incorporated this idea into its own decision making process?

How, you ask?

Imagine you’re hurrying to work. Just as you’re about to get inside the car, you realize you’ve forgotten your keys. This is Evidence. Something has happened that is pertinent.

You’re quite certain it’s somewhere in the house, but there are a lot of places. Remember, you’re really late. You do not have the luxury of time to comfortably search for it. So what do you do immediately without even thinking about it? You recall places you could have possibly kept it. They are called Priors.

Now, you don’t bring the washroom, the store room or the prayer room into consideration. It’s quite impossible that you could have mislaid it there. The probability is zero. But, there are other places with more chances.

This, my friends, encompasses the idea of the Bayes Theorem.

Our prior beliefs have an effect on the probability of each Prior. And this is what Bayes attempts to quantify.

The provenance of this exquisite concept came from Reverend Thomas Bayes.

Born in the 17th century, around 320 years before today, there is no clear image of what he looked like. To know more about him, this link The Reverend Thomas Bayes, FRS: A Biography to Celebrate the Tercentenary of His Birth can be a source of immense information. Although he was touted to be a brilliant mathematician, this was not the trajectory he took up in his life. A man of strong faith, his only focus was in attempting to answer questions about god. His first publication was a theological work, “Divine Benevolence”, although the lack of specification of the author presented ambiguous evidence as to if he really wrote it, contrary to the widespread belief that he in fact did. His divine beliefs aside, he became more and more involved with mathematics and its related fields soon enough.

Thomas Bayes truly didn’t understand the implications of his work, nor that it’d be most used widely 300 years later.

“On the death of his friend Mr. Bayes of Tunbridge Wells in the year 1761, he was requested by relatives of that truly ingenious man, to examine the papers which he had written on different subjects, and which his own modesty would never suffice him to make public. Among these Mr. Richard Price found an imperfect solution to one of the most difficult problems in the doctrine of chances, for ‘determining from the numbers of times an unknown event has happened and failed, the chance that the probability of its happening in a single trial lies somewhere between any two degrees of probability that can be named.’ The important purposes to which this problem might be applied, induced him to undertake the task of completing Mr. Bayes’ solution; but at this period of his life, conceiving his duty to require that he should be very sparing of the time which he had allotted to any other studies than those immediately connected with his profession as a dissenting minister, he proceeded very slowly with the investigation, and did not finish it till after two years; when it was presented by Mr. Canton to the Royal Society, and published in their Transactions in 1763.—Having sent a copy of his paper to Dr. Franklin, who was then in America, he had the satisfaction of witnessing its insertion the following year in the American Philosophical Transactions.—But not withstanding the pains he had taken with the solution of this problem, Mr. Price still found reason to be dissatisfied with it, and in consequence added a supplement to his former paper; which being in like manner presented by Mr. Canton to the Royal Society, was published in the Philosophical Transactions in the year 1764. In a note to his Dissertation on Miracles, he was availed himself of this problem to confute an argument of Mr. Hume against the evidence of testimony when compared with regard due to experience; and it is certain that might be applied to other subjects no less interesting and important.”

Bayes embarked on a solution and his close aide Richard Price finished it. Price believed the result provided proof for the existence of god and that was a primary facilitator for his own work on this.

The concept was initially termed as Inverse probability, ‘Bayes’ was prefixed to this concept only much later on.

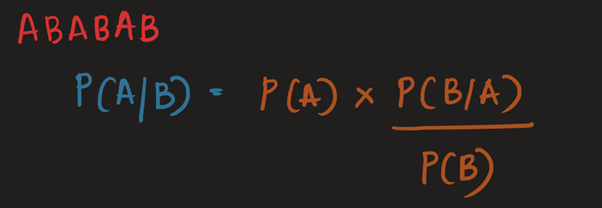

Let us first begin with the formulae –

I like to remember the formula with the help of this tiny tip, ABABAB.

- A and B are 2 events which have non-zero probabilities. Implying, they have some probability of occurring.

- Note that P(A) & P(B) are marginal probabilities (Not dependent on anything else occurring), and the other terms are conditional probabilities.

Let’s derive this, intuitively shall we?

We know some of our emails are being categorized as spam by default. Sometimes, it can be pretty annoying but Bayes accurately explains how the system does its demarcation.

Let us simplify it a lot.

Suppose, we discover that most e-mails that contain the words “Prince” are spam.

However, there are emails that contain the word “Prince” and yet are NOT spam, also known as False positives.

Given this information, can you find out the odds of it being spam IF the word “Prince” is used?

Prior probabilities :

P (Spam emails) / P (Not spam emails)

Assume around 20% of emails are spam.

So, 0.2/0.8.

Strength of new evidence :

P (E-mail has the word “Prince” but is spam) / P (E-mail has the word “Prince” but is not spam)

Assume around 60% of spam emails contain the word “Prince”. Around 25% of normal non-spam emails contain the word “Prince”.

Now all you have to do is plug in the numbers.

Prior probabilities * Strength of new evidence.

New probability : P(Spam E-mail/E-mail has the word “Prince”) / P(Not spam e-mail/E-mail has the word “Prince”)

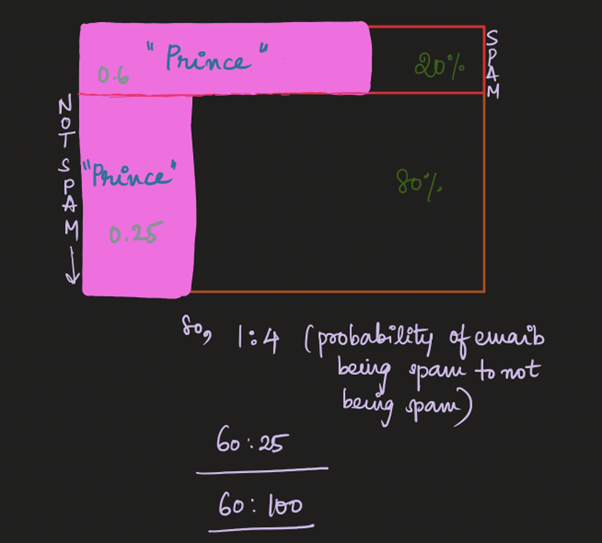

For me personally, Julia Galef is a chief reason behind me trying to understand the beauty that is Bayes. Her usage of the “Box” as I’d like to call it, is incredibly helpful in trying to use the formula intuitively.

So, around 60% of the emails that contain the word Prince are spam or every 3 out of 5 spam emails contain the word Prince.

When you filter spam based on the use of certain words, it is very limited and the chance of false positives are highly likely.

But if we use BT, we look at it as probabilities.

Instead of posing a binary answer question (yes/no), we compute the chance of an email being spam. If an email has a 99.99% chance of being spam, it probably is.

Here at this point, machine learning comes into play and the filter will keep updating the probabilities that some words lead to spam messages. Advanced Bayesian filters can examine multiple words in a row.

Can we compare the formula with this intuitive explanation?

You have a hypothesis. You observe evidence. You want to know the present probability of the hypothesis you held given new evidence. So, the goal here is, you’re restricting your views only to areas where the rules hold. The pink rectangles.

Step 1 – Find out the probability that the hypothesis holds before considering new evidence —- Priors.

Step 2 – FIND OUT THE PROBABILITY THAT WE’D SEE THE EVIDENCE GIVEN THE HYPOTHESIS IS TRUE. The pink rectangles. P(E/H) and P(E/Not H).

Step 3 – Calculate posteriors.

P (H/E) = P (E/H)P(H) / P(E/H)P(H) + P(Not H)P(E/Not H) = P(H)P(E/H)/P(E) – Total area meeting the evidence.

Convert the odds into percentage, you will get your answer.

P (Spam/ “Prince”) => P (Spam) * P (Prince/Spam) / P (Prince)

- 0.2 * 0.6 / 0.32 (Using Total probability Rule ; 0.25 * 0.8 + 0.6 * 0.2)

- 0.375 (Or) 3/8

I believe there are 2 perspectives of this concept here.

- You can use this to confirm the validity of a hypothesis.

- It is incredibly helpful to use this theorem when trying to quantify changing beliefs, i.e. given new evidence, how can you update the prior probability you had assigned to priorly held beliefs?

Both are essentially the same thing, simply different ways of looking at a scenario.

What you should keep in mind about the bayes theorem is that the new evidence should only update your priors which you must always take into account. It should not affect your beliefs completely.

Okay, Google.

Suppose you notice a few symptoms (Evidence) and you google them. You get a wide range of possible diseases (Hypothesis). But if you went to an actual doctor, she’d take into account your health characteristics and attributes prior to the symptoms occurring and then give you a solution. This is the bayes theorem at work. Some diseases are more probable to occur given certain probabilities of priors. For instance, if you were a non-smoker and had never been exposed to smoking, there would be a lesser chance of you having lung cancer even if you exhibited the symptoms related to it. Google would not have access to your prior history and hence wouldn’t give you an accurate result as opposed to a doctor who would.

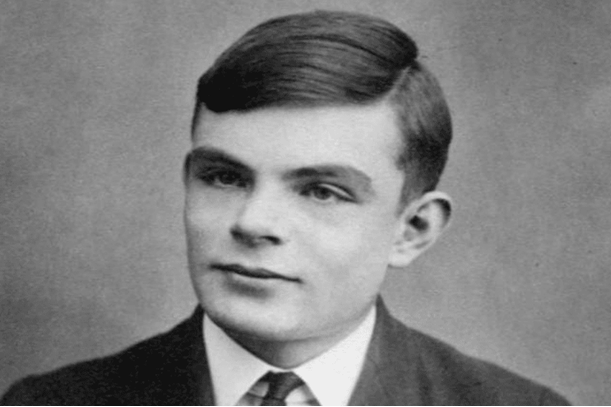

Did you know Alan Turing helped the Allies win the war against Germany with just this simple concept?

Alan Turing played a key role in helping the Allies win the war against Germany using a simple idea. The Germans used a complex system called the ‘Nazi Enigma code’ to send secret messages. The Enigma machine changed its settings every day, so even if someone cracked the code, the information would be useless by the time it was decoded. This made it almost impossible to break the code—until Turing had a great idea.

He realized that some messages were more likely than others. By studying previous decoded messages and using logic, he figured out that certain phrases, like “Hail Hitler” or “The weather report for today,” were often used. Once Turing’s team found these patterns, it made it easier to guess the rest of the code, since letters couldn’t be encrypted the same way.

It wasn’t easy, though. Turing created a new machine to help break the codes faster. He understood that, unlike machines, humans make predictable mistakes or follow patterns when using language. Even if the Germans changed their methods, Turing knew there would still be some predictability, and this helped him crack the code and change the outcome of the war.

The Bayes theorem is pertinent because it deliberately forces us to account for other possible explanations. It doesn’t tell you something is true just because you find evidence corroborating it. It looks at how probable these explanations are and the conditional probability of the evidence on our explanations.