I came across the term tulip mania for the first time in a derivatives text. It claimed the tulip mania that occurred in the 1600s was a direct example of futures being used. It has also been widely acknowledged to be one of the first instances of a speculative financial bubble, in both economic and financial literature and frequently used as a tale of caution indicating the perilous consequences of a free market. There was even a film made in its backdrop, “Tulip fever”, based on a novel of the same name by Deborah Moggach. And well, it piqued my interest, because after all these were just tulips, a commonplace flower. Although extraordinarily beautiful, it just did not make sense. So, I had to know more.

Upon researching, I notice the multitude of extravagant tales spun on this topic.

Ostensibly, a sailor once mistook a tulip bulb for an onion and consumed it with his sandwich. The poor fellow was then thrown into prison for this egregious “felony”.

One of the primary catalysts was the Semper Augustus flower, commonly called the “Broken bulb” derived its appeal from the pattern of its petals. This striped, multicoloured flower which was actually caused by a mosaic virus strain making it even more rare, at one point had more worth than a mansion in fashionable Amsterdam, complete with a garden and coach.

As the market for tulips grew, speculation also exploded. This Tulip craze seemed to completely consume all levels of the Dutch Society in the 1630s, everyone from the lowest dregs to upper royalty simply had to have a part in this. Traders began offering exorbitant prices for bulbs. Since tulips were not available all year long, people got into contracts to purchase the bulbs when available at a specified price (Or as is now known, forward contracts, futures really because not only was it standardized but the Dutch government were keen on enforcing it.) some even heavily margined. Companies were formed just to deal in tulips. It seemed at the time that the price could only go up; that “the passion for tulips would last forever.”

But, by February 1637, the tulip prices had fallen tenfold. As we will later see, it kept falling till it was about 1/20th of their all-time high. By May, this value had become 11 guilders and stayed there. Seems like a bubble.

Scottish journalist, Charles Mackay in his popular 1841 work “Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds” precipitated the crowning of these scenes as a mania and as an alleged “bubble”. He and his work has been subjected to much scrutiny as to the veracity of his claims, but even after years, the Dutch tulip mania has not yet been unseated from being used as bubble jargon.

So, at this point, I’d like to place two questions forward for introspection:

- What is a bubble?

- What exactly happened in the “Tulip mania”? How much of it was fact and how much fiction?

Let’s begin with the first one. What is a bubble?

I had always been under the assumption that a bubble was a phenomenon with substantial proof. And this outright ignorance became amusing as I read on.

Although a widely acknowledged concept, it still is extremely hard to provide a prim and proper definition of the term because over the course of time, everyone has had their own view. Whether a particular episode could be termed a bubble, was always heatedly debated over. There are as many bubble proponents as there are hostile sceptics positing it as unscientific. Garber (2000) cautions that “bubble explanations should be a last resort because they are non-explanations of events, merely a name we attach to a financial phenomenon that we have not invested sufficiently in understanding”.

Let’s take an asset A. The value of A can be either its ‘Market Price’ or what is commonly known as ‘Intrinsic Value’. The latter is nothing but the present value of all the potential cash flows that can be expected to be received from A. For a stock, we look at its dividends and its terminal value.

When the market price never deviates from this inherent value, when it is never given an appropriate window to do so, we find testimony of what we call an “Efficient Market” as propounded by Eugene Fama. People are paying for what it’s really worth.

BUT, if we can find evidence of A persistently diverging, this is where the conjecture of a bubble takes place. Obviously, this can be determined only after it has occurred.

Bubbles can be facilitated by 2 thought processes.

- Irrational Exuberance: The term was popularized by former Fed chairman Alan Greenspan in his 1996 speech, “The Challenge of Central Banking in a Democratic Society.” The phrase was interpreted as a warning that the stock market might be overvalued. The Tokyo market was open during the speech and immediately moved down sharply after this comment, closing off 3%. Markets around the world followed. Yale economist Robert J Shiller used it as the title of his book, Irrational Exuberance, first published in 2000, where Shiller states:

“Irrational exuberance is the psychological basis of a speculative bubble. I define a speculative bubble as a situation in which news of price increases spurs investor enthusiasm, which spreads by psychological contagion from person to person, in the process amplifying stories that might justify the price increases, and bringing in a larger and larger class of investors who, despite doubts about the real value of an investment, are drawn to it partly by envy of others’ successes and partly through a gamblers’ excitement.”

This definition is a quite comprehensive elucidation about what irrational exuberance implies. Isaac Newton, for example, who in addition to his many well-known accomplishments was also a disappointed investor in the South Sea Bubble, opined that “I can calculate the motions of heavenly bodies, but not the madness of people.”

Malkiel (1985), Random Walk Down Wall Street, the famous Wall Street investor of the early 1900’s, took an even dimmer view of the rationality of the market, opining: “Anyone taken as an individual is tolerably sensible and reasonable – as a member of a crowd, he at once becomes a blockhead”.

- The next one would be Regret theory or what millennials call FOMO or Fear of missing out. This is a psychological fear of regret which can either be a positive or a negative impetus. It can either motivate someone enough to do something or scare them enough to not do it, especially for an investor which it is a significant influence. This is especially true for an extended bull market. For explanation, in the context of a stock market, suppose Mark tells his friend Rahul to buy a certain stock A that he considers to be on a rise. Rahul being cautious, might hesitate to do so. On the off-chance A’s price does rise as predicted, Rahul would be inundated with regret of having missed an opportunity to profit. So, the next time Mark says something, Rahul might not heed his conservatism and proceed to buy it without taking the time to warrant the merit of the recommendation.

Both these reasons cause, what is called an “Irrational bubble”.

However, consider this. If you can find solid vindication of an asset’s prices exhibiting bubble behaviour and believe you can profit off of this change in price by “Riding the bubble”, this incites what is called a rational bubble. This pushes the price higher, inducing this rational bubble to persist. So, if you transact in a bubble while remaining cognizant of the fact that it is overvalued, then it is not irrational now is it? This is augmented by the “Greater fools’ theory”. According to it, without any regard to the its actual virtues, any transaction can be made profitable as long as you have a buyer or a greater fool who is willing to buy the asset at a higher price, which is an astute argument.

Whatever the case, “bubbles” are bad news. The decline can be precipitous and abrupt causing irrevocable damage to one’s property. Bitcoins are a good example of this fact.

I chanced upon Maureen O hara’s paper in the Review of Financial Studies, Jan., 2008, where she had unique insights to this.

- Ratifying my previously stated fact, she finds that there is no one way to define a bubble.

- But if we can’t define it, do we at least know a bubble when we see one? As much as any authority would like to believe they do, nope.

- What causes bubbles? There is a long history of potential explanations to this question. Adam smith in 1776 was of the opinion that it was caused by overtrading. (Made sense back then). Lord Overstone, writing in the 1860s, explained asset price behaviour as arising from a cycle, beginning with quiescence, and then moving on to improvement, confidence, prosperity, excitement, overtrading, convulsion, pressure, and stagnation, before returning finally to quiescence. And so on. But the case remains that none of them are truly definitive. Nothing yields an operational way to establish empirically the existence of a bubble, nor do they provide a basis for predicting the emergence of such a phenomenon.

- Her ending remark made a lot of sense in this context.

“Are there bubbles? Are markets really irrational? I am not sure. I do know that markets are very hard to predict and thus can seem “irrational.” But I prefer a more neutral view. To correct Keynes, “Markets can remain intransigent longer than you can remain solvent.” Perhaps the best advice, quoted in Malkiel’s Random Walk down Wall Street, is Oskar Morgenstern’s dictum that “A thing is only worth what someone else will pay for it.” This will be true whether in a bubble or not.

So, there is still no consensus among economists as to whether bubbles can exist in modern asset markets or even how to distinguish between rationality and irrationality when it comes to bubbles. But however, the fact remains that sometimes asset prices do inexplicably deviate far from its theoretical fundamental value, as corroborated by the Dotcom bubble. This altercation about bubbles will never find a proper answer. We can only ensure we do our due diligence.

Speaking of deviation, I have unfortunately committed the same error as well. Let us go back to the tulip mania. What is the truth to it?

Dr Anne Goldgar decided to test the veracity of all these legends while researching for her book Tulipmania: Money, Honor, and Knowledge in the Dutch Golden Age.

She casts serious doubts on its “Bubbleness”. She does not find concrete evidence of the entire industry collapsing. Even though merchants really did engage in frantic tulip trade and paid incredibly high prices for some bulbs. The market did fall apart and cause a crisis, but she chalks it upto a a sense of betrayal about the breach of trust. Social relations were undermined, and this caused the entire foundation to shift. As we will later see, people decided to change their minds regarding payment of final value. This planted a permanent seed of doubt amongst all traders later on. Why was it made out to be a calamity? Instead, the story has been incorporated into the public discourse as a moral lesson, that greed is bad and chasing prices can be dangerous. It has become a fable about morality and markets, invoked as a reminder that what goes up must go down. Moreover, the Church latched on to this tale as a warning against the sins of greed and avarice – it became not only a cultural parable, but also a religious apologue.

On this note, I read 3 papers – Famous first bubbles & Tulip mania (Peter M Garber), and The Tulip mania: Fact or Artifact? by Earl Thompson. I’d like to focus on Thompson’s article who encompasses Garber’s opinions, and attempts to correct his shortcomings and builds on it to come to the same conclusion, that contrary to public opinion the Tulip mania was not a bubble at all.

Peter Garber tries to provide reason lays the foundation by positing that even modern-day markets for flowers can command exorbitantly high prices.

Thompson’s convinced that the TM was nothing but an “artifact” of a mandatory conversion of original future contracts to option contracts by the Dutch courts. There was nothing maniacal about the prices in this period. On the contrary, the market was impressively price efficient and fundamentally driven. Both his rational explanation and quantitative proof of this fact is quite interesting to read.

First, lets look at what really happened.

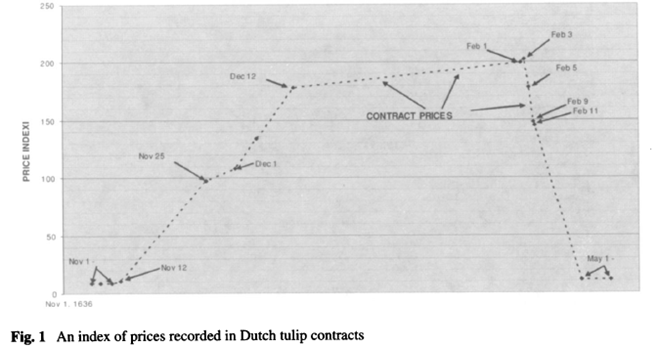

The graph above represents the Tulip mania bubble in the time period it was purported to have occurred.

Here, Thompson takes a quality price weighted index (The quality of the bulbs sold, and its price was taken into account) to represent it.

So, the tulip flowers were commonly planted in the fall (Sept – Dec) and dug up in the spring (Mar – June). In this context, the prices as shown in the graph could not possibly be cash contracts, rather contracts for future delivery or futures. As you can see, contract prices rose to new heights until the news that trading was going to be suspended reached the market, resulting in a further fall of prices until the actual trade suspension on February 5th 1637. Now, there were no basic economic shocks over this relatively short span of months, it clearly must be a bubble. The prices do not seem to accrue to fundamental values.

But, Thompson asserts that appearances can be deceiving.

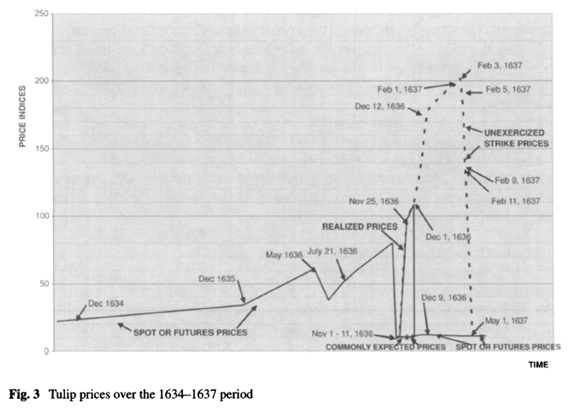

Take a look at this graph. The broken line is the futures prices as shown in figure 1. And superimposed on it is another graph showing a solid line for the actual prices paid to the planters. See how the divergence only seems to grow larger after November 30th. Why?

Because the legislatures had taken a decision to amend the original future contracts, particularly ones entered into after November 30th to include a new provision. This provision relieved the buyers from their unconditional contract obligations to buy the tulips at the specified contract prices.

As one question is answered, another arises. Why did the Legislatures breach the planters trust in them? Why did the approve of this buyer favouring conversions of contracts?

To answer that, we must go further back in time to 1634 – widely acknowledged to be the initial stages when the prices of tulips started rising, significantly over those of the previous year.

Look at the graph. Notice the prices rising constantly upto sometime in October 1636. The literature from around this time interval proclaims far-reaching frenzy and surging public participation of zealous traders, even public officials, Or Dutch Burgomasters. The sellers for the most part constitute professional tulip planters and tenders – Ones who had purportedly done quite well for themselves in the rising market. This consistent rise could very well be attributed to the German optimism about the war(The thirty years’ war) they were currently fighting against the Swedes. They had been successful in pushing the latter back for some time. This was further augmented by Germany’s receptive climate for these new flowers and as evidenced by a multitude of 17th century paintings, the nobles were big fans of tulips and had even taken to meticulously planting and tending to them.

However, in October, you can notice prices dangerously collapsing, even to levels below that of 1634 prices. Why would this happen out of the blue when everything was going so well?

The Germans, who had until then been riding a victorious streak surprisingly suffered a resounding defeat by the Swedes at Wittstock which changed the course of the war. This was further followed by peasant revolts and the rebel army becoming more active.

Naturally, the enormous prospective demand for tulips that had been evident until then, crumbled. Everyone, including the princes started digging up their bulbs to try cashing them in turn causing the supply in the market to increase. In view of these fundamentals, it was logical for the prices to plummet to 1/7th of their October 1636 peak by early November.

Once, prices plummeted, the investors especially the public officials began losing money. It was a huge financial disaster. Remember, that most of these transactions had been carried out with futures. Apart from having to pay above market prices for when bulbs were to be delivered, wanting a part in the rising market for tulips, they had leveraged themselves tremendously.

But they would not go down without a fight. After all, the planters had already become rich in the prior extended upturn, they could afford losses.

So, these politically connected investors started congregating in an attempt to figure out a solution to this “Problem”.

Initially they threatened to completely nullify the contracts, so no one has to pay anything. But the planters were also not without political clout and pushed back.

Ultimately both parties ironed out a deal whereby the unconditional obligation to purchase bulbs at the preconceived contract price would be converted into an opportunity to do so, and if the market price was below the strike price the planters would be compensated for this loss by payment of a fixed percentage of the contract price. In current parlance, the futures were to be converted into Options.

See, news of these deliberations had slowly started to seep into the market by late November. And contract prices soared to reflect this conversion to a call option exercise price. It worked as normal options would. The contract price would not need to be paid if the spot price of the tulip bulbs were less than it.

When it is evident that a future has been remoulded to an option, the contract prices will rise. Why? If the planters knew, the investors would only pay the fixed percentage, they would significantly jack up the contract price in hopes of recovering the spot price. And people would be willing to invest. Why?

The percentage had not been decided yet, but everyone knew the range would be around 0-10%. So, Worst case, the spot price would be lesser than the contract price – The maximum that’d be lost is the fixed percentage they’d have to dish out. But, If the spot prices became greater than the contract price, they could make an instant profit for a minimal 0-10% risk. And by February, the price had risen 20 times. Thompson touts this to be the cause of tulip mania.

The negotiations to decide the specified percentage took quite a while until February 24th. The Dutch officials finally agreed with the planters’ demand to convert only contracts after November 30th (A date by which virtually all traders had became cognizant of the conversion) and not October as was publicly supported in exchange for a mere 3% of the contract price.

This deferment of a month beyond the public officials’ previously announced date, favoured the planters and also speculators who sold contracts in November to unwitting buyers who assumed they were buying an option but were forced to pay the falsely assumed exercise price as a futures price. Most of these speculators were the public officials, who being privy to more knowledge easily offset their losses. The innocent buyers and not the planters as intended were the real victims.

So, this boom and bust was no irrational behaviour that could be accredited to the speculative delusions of the people. Not only does all this information purvey enough fundamentals as is necessary to warrant this price pattern but also gives substance to the presence of a rational expectations assumption.

Depicting the tulip mania as an economic horror story is completely unfounded and coining it as a bubble would be specious, especially when the tulip market proves to be overwhelmingly efficient for the 17th century. The option prices quite closely approximated the expected costs to the informed suppliers who only expected to receive the solid line prices in figure 2, which is remarkable given how previously experienced losses should have taken precedence in investors’ minds and led to inefficient price patterns.

The tulip mania was nothing as the legends claim.